By Will Thibeau, Army Ranger veteran

First published on Tom Klingenstein’s website. His Note: Understanding our present situation, and the road by which we arrived here, is the necessary precondition for developing a sound strategy. This is as true in a cold civil war as it is in conventional warfare. It is fitting, then, that we should examine how our military establishment came, over decades, to supplant the conventional wisdom of warfare with the ideology of the group quota regime. Will Thibeau examines that inexorable march through one of our most vital institutions, and sees a clear lesson for those who hope to restore our Armed Forces to their former standard of excellence.

PART ONE | PART TWO | PART THREE | PART FOUR

Part III of Identity in the Trenches: The Fatal Impact of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion on U.S. Military Readiness

The transformation of the United States Armed Forces over the last century has been as radical, as sudden, and as thoroughgoing as virtually any experienced by a military body in all of recorded history.

Over the course of two world wars, the demands of combat at unprecedented scale sped along the integration of both racial minorities — especially black Americans — and women across every branch of the Armed Forces.

It took less than a generation, however, for this integration (and the principles of color-blindness that emerged from it) to be overtaken by a new social imperative: proportional representation, enforced by group quotas and later the widespread framework of “DEI.”

No longer would it be enough for the military to select the best of the best, regardless of race or other innate factors.

Under the new regime, the Armed Forces became a representative institution, one whose political/racial composition — modeled on that of the nation at large — took priority over its warfighting capabilities.

This pivot was accomplished largely by successive commanders-in-chief, starting with Harry Truman and carrying on through the Johnson, Carter, Clinton, Obama, and Biden administrations. The transformation, however, cannot be blamed entirely on progressive presidents.

Civil Rights-era Supreme Court decisions, racial conditions on funding imposed by Congress, initiative by the military bureaucracy, interference by outside activist groups — all these and more were essential to turning the merit-based force that won two world wars into an identity-centric institution that has not seen a major victory since 1991.

Today, the drive for proportional representation colors every action of the military establishment.

Recruiting strategies are crafted with racial targets front of mind, and the entire DoD approach to personnel now revolves around identity groups.

Each branch now works actively to increase the representation of women and minorities in the most critical roles, including aviation, combat operations, and the highest echelons of command. This identity-based decision-making is mutually exclusive with the singular insistence on merit that undergirds any strong military force.

The danger of this status quo is clear. In order to chart a path forward, however, we must understand how we got here.

The extent and coordination of the decades-long effort to create this new military are remarkable — and should remind us that any effort at reform must be every bit as deliberate and far-reaching.

How Integration Gave Way to Racial Quotas

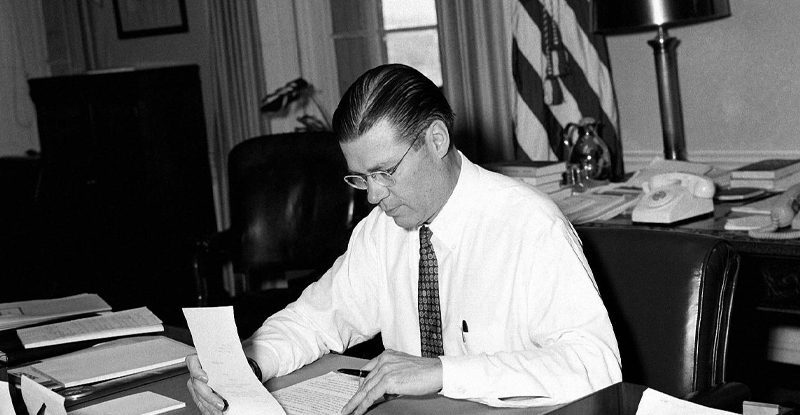

President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981 on July 26, 1948. The executive order established that there should be “equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.”

According to modern advocates of race-based decision-making, President Truman started an uninterrupted progressive march to provide for proportional representation in the military. The reality of the military’s implementation of E.O. 9981, and the radical departure from such principles of equality in the 1960s, tells a vastly different story.

Much of the immediate follow-on to E.O. 9981 is hard to believe in light of the turmoil of the ‘60s and the race-obsessed culture that followed.

The Army removed race designators from personnel files to ensure non-discrimination, and the military spent legitimate organizational energy seeking to choose and promote the best, regardless of race.

If the common trope of race-blind decisions was ever a reality, it was in the years after Executive Order 9981.

As history goes, however, the Washington bureaucracy quickly planted the seeds of more aggressive racial policies.

The first post–E.O. 9981 policy decision that implemented racial quotas was Executive Order 10308, on Improving Compliance in Federal Contracts. Issued in 1951, amid the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement, E.O. 10308 was a response to growing demands for racial equality and non-discrimination. This executive order aimed to improve compliance with non-discrimination provisions in federal contracts, setting a precedent for subsequent affirmative action policies.

Prior to this executive order, there were unofficial racial quotas dating back to 1918. These unofficial quotas were put in place to limit the number of black enlistees. The general sentiment was that African Americans should not exceed a certain percentage of the total military force, correlating with their percentage of the general population, which was about 10% at the time.

During the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, the U.S. and the military saw a vast expansion of affirmative action laws. In 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, on Equal Employment in the Military. The focus on equal employment opportunity in the military was influenced by the ongoing debate about the role of African Americans and other minorities in the Vietnam War, where they were disproportionately represented.

This executive order led to an overcorrection by Secretary McNamara in 1966. In seeking to implement E.O. 11246, the DoD established an Equal Employment Opportunity program, which represented a strategic effort to institutionalize affirmative action within the DoD.

The Pentagon also introduced Special Emphasis Programs (SEPs), targeted initiatives designed to ensure equal opportunity and promote diversity and inclusion within the armed forces. These programs focus on specific groups that have been historically underrepresented or have faced discrimination. SEPs aim to address issues related to recruitment, retention, training, and career development of members from these groups, fostering a more inclusive and diverse military environment.

The most far-reaching racial initiative of this era was McNamara’s Vietnam recruitment plan, Project 100,000. This project aimed to enlist individuals who previously did not meet the standard mental and physical criteria for military service by lowering the Armed Forces Qualification Test (AFQT) scores required for enlistment and relaxing some physical standards.

The program primarily targeted young men from inner cities, which led to an outsized proportion of minority recruits. It also raised concerns and criticisms regarding the preparedness and treatment of these lower-aptitude, newly eligible recruits, both during and after their service.

McNamara explicitly charged the military with leading the government-wide adoption of the spirit of the Civil Rights Act by ensuring the military’s demographics mirrored those of the nation.

This started with a mandate, originating from the Defense Race Relations Board, that West Point select admissions classes that mirror the demographics of the nation. The nation heard little about this initiative until recent years when various Army officials testified in Congress to the enduring existence of “class composition goals” for admissions — a direct continuation of McNamara’s policy.

Hot on the heels of Project 100,000, in 1971, the Supreme Court case Griggs v. Duke Power Co. addressed workplace discrimination and invented the doctrine of disparate impact. The principles established in Griggs v. Duke Power Co. significantly influenced military policies, ensuring that recruitment, promotions, and assignments would be evaluated for any potential racial disparity, even indirect and unintentional ones.

This led to even more direct targeting and affirmative action practices in the military. No longer would the color-blindness of E.O. 9981 suffice. Under the doctrine of disparate impact, anything less than equality of outcome left an institution open to accusations of racism — effectively making group quotas, the guarantee of outcome equality, the military default.

The same year saw the establishment of the Defense Race Relations Institute (DRRI), later rebranded as the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute (DEOMI). DEOMI is a U.S. Department of Defense joint services school that offers courses on equal opportunity, intercultural communication, religious, racial, gender, and ethnic diversity and pluralism.

In the 1972 NDAA, Section 2000d-1 prohibited discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, or religion in any program receiving federal financial assistance. Again, the nominal demand for color-blindness quickly gave way to policy explicitly favoring certain identity groups.

The 1986 NDAA added Section 1207, which required the Secretary of Defense to submit an annual report to Congress outlining the department’s efforts to promote minority and women-owned businesses in defense contracting. This provision expanded the DEI revolution from the uniformed services to the private defense sector.

In 1992, Bill Clinton campaigned as an antagonist to the defense establishment in his pledges to open the military to homosexuals and other diversity initiatives. While initial resistance from the brass stalled the full extent of what Clinton promised on the campaign trail, the administration carefully crafted military policy to remake the institution in the image of the progressive left.

This reconstruction began with the 1994 NDAA, where Section 802 required the Secretary of Defense to establish a mentor-protégé program to assist small, disadvantaged businesses in the defense industry. The program aimed to enhance the participation of historically underrepresented groups in defense contracts by providing support and guidance from established defense contractors.

In 1995, the Military Equal Opportunity (MEO) program codified the previous 30 years of change in DoD policy. The directive focused on diversity and inclusion within the military ranks. It addressed civil rights organizations advocating for equal treatment and opportunity for promotions in the military by ensuring every program, office, and personnel process was designed to serve the sacred cow of proportional representation.

The George W. Bush administration invested heavily in the military, but largely left the liberal direction of the institution unchanged as the nation grappled with Islamic terrorism at home and two wars abroad.

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was famously antagonistic and ambivalent toward the generals, even during a significant period of growth for the military industrial complex. It was during the Bush administration that the Army convened its Diversity Task Force, whose final report laid the theoretical and practical foundations for 21st-century military DEI.

During the first few months of the Obama administration, the Pentagon established yet another new program through DoD directive 1020.02, emphasizing Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity.

In many ways, this directive made explicit the distinction between Truman-era equal opportunity and Obama-era race radicalism.

The rationale — the same one set forth by Bush’s Diversity Task Force — was that a diverse military is actually a stronger and more effective one. The increasing complexity of global military operations, the line of thinking went, necessitated a force that reflects and understands the diverse nature of global societies. Today, this principle remains at the center of DoD policy and strategy; it remains, more to the point, an assumption without evidence.

The Long, Winding Road to Women in Combat

The United States saw the first official enlistment of women in the military during World War I, when the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps allowed women to serve primarily in clerical positions. The Army Nurse Corps, established in 1901, also played a significant role during this time.

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC), the U.S. Navy’s Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, and the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve (SPARS) were all established during World War II. These organizations allowed women to serve in a wide range of non-combat roles, from clerical to mechanical to flight instruction, filling many traditionally male roles as men were needed on the front lines in unprecedented numbers.

Three years after the war’s end, the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act, signed by President Truman, made these emergency accommodations permanent. Women were authorized to serve as permanent, regular members of the Armed Forces, not just in auxiliary or temporary positions, though they were still limited to certain non-combat roles.

An important aspect of this act was its impact on physical fitness requirements for women in the military. The legislation necessitated a reevaluation of these standards to accommodate and fairly assess female service members, acknowledging physical differences while also ensuring operational effectiveness.

In the 1960s, while affirmative action along racial lines became a key national cause, the revolution in the role of women in the military proceeded largely unnoticed. Signed by President Johnson in 1967, Executive Order 11375 expanded the object of affirmative action directives resulting from the 1964 Civil Rights Act to include sex, in addition to race.

The Defense Manpower Commission, established in 1974 to conduct a comprehensive study of the manpower requirements of the Department of Defense, often served as a readiness cover for achieving sex diversity in the military. With the explicit aim of recruiting more women, the Commission pursued several initiatives:

- Recruitment Methods and Techniques: Clause (6) focuses on the methods and techniques used to attract and recruit personnel. This is crucial for women and minorities as it offers a platform to address potential biases in recruitment and to develop strategies that ensure diverse and inclusive enlistment practices.

- Socio-Economic Composition of Military Enlistees: Clause (7) addresses the implications of changes in the socio-economic composition of military enlistees since new recruiting policies.

Issued in 1980 by President Jimmy Carter, Executive Order 12250 focused on the leadership and coordination of nondiscrimination laws by establishing a formal directive to pursue gender equality reflected in society. It aimed to ensure effective implementation of civil rights laws across federal agencies, including those governing the military.

In Rostker v. Goldberg (1981), the Supreme Court upheld the male-only draft, answering a major question posed by Congress in the 1980 NDAA. Despite the result, the episode is remarkable: to even ask the question of women in the draft indicated a sea change.

In 1992, Congress created the Presidential Commission on the Assignment of Women in the Armed Forces, which sought to “conduct an independent bipartisan, fair assessment of the laws and policies affecting the assignment of women in the military.”

Then in 1994, President Bill Clinton rescinded a longstanding rule that prevented women from serving in roles that exposed them to undue, combat-related risks. This effectively opened all roles but those directly engaged in ground combat to female service members, radically altering the capacity in which they served and potentially opening a door to future combat service.

In another major case, United States v. Virginia (1996), the Supreme Court compelled the Virginia Military Institute to admit women for the first time since its founding in 1839, challenging long-standing male spaces in military education. U.S. v. Virginia not only impacted VMI but also set a legal precedent that drove policy changes across military academies and educational institutions.

Section 592 of the NDAA for Fiscal Year 1998 highlighted the increased role of women in the Armed Forces and acknowledged concerns about gender inequalities. This section endowed research focused on the characteristic mission of “disparate impact” inquiries, to find injustice wherever inequality is present.

ACLU v. Department of Defense (2004) was a pivotal case that challenged the policy excluding women from combat roles in the military. While the case itself did not directly lead to a policy change, it was part of a series of efforts and discussions that culminated in the Department of Defense lifting the combat exclusion for women in 2013. Notably, major activist groups like the ACLU were crucial in these efforts, lending resources, publicity, and credibility to the calls for transformation.

Prior to the 2015 NDAA, women were formally excluded from serving in direct ground combat roles. Section 524 of that year’s NDAA repealed this policy and directed the Department of Defense (DoD) to eliminate all gender-based barriers to service.

The 2016 NDAA (Section 525) required the DoD to provide Congress with a plan and timeline for integrating women into all combat positions. This section sought to ensure that gender-neutral standards were applied during the integration process.

Just twenty years after Clinton’s opening all non-combat roles to women, and a mere hundred after the arrival of the first enlisted nurses, the military is now obligated to ignore any differences between men and women, treating male and female service members as the same and interchangeable for any purpose.

This requires the denial of natural, observable differences in physical ability, in temperament, and in all manner of relevant metrics and qualifications.

In fact, to counteract these natural differences, the military again imposes group quotas, to ensure that proportional representation is achieved regardless of disparities in merit.

As with racial quotas, the obvious and inevitable effect is a less ready force and a less secure nation.

Learning the Lessons of the Past

Looking back on a hundred years of military history, it is all but impossible to point to a single moment and say with any confidence that “this is where it all went wrong.”

Racial integration and the introduction of female service members were driven by the pressing need to find and train the best of the best, but the transition to “representation” and “diversity” as military ideals in themselves ensured that this color-blind, merit-based military would be short-lived.

An onslaught of court cases, legislative demands, and sweeping presidential reforms followed, ensuring over the course of decades that the military would be transformed.

There is no single policy or decision that can be reversed to restore the primacy of merit in our Armed Forces. That would be too simple.

The current state of affairs is the sum of dozens of policies, initiatives, and accidents spread over generations.

A functional strategy must understand and address them all — and, most importantly, must be prepared to fight the ideology that underlies them, to tear out wokeness from our military root and branch.

First published on Tom Klingenstein’s Website

Leave a Comment