By STARRS member Jane Hampton Cook

One problem with Critical Race Theory (CRT) is that there is no room for forgiveness or growth. You’re either born an oppressor or are oppressed based on your skin color and cannot change.

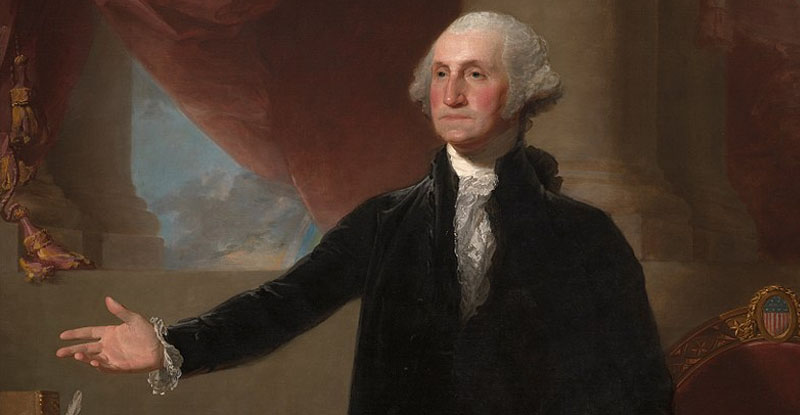

This cultish fallacy ignores the central truth that to be human is to grow and change. For example, although George Washington was born into a slave-owning family, he died freeing the slaves under his direct care.

“When he drafted his will at age 67, George Washington included a provision that would free the 123 enslaved people he owned outright. This bold decision marked the culmination of two decades of introspection and inner conflict for Washington, as his views on slavery changed gradually but dramatically,” Mount Vernon scholars explain.

When and why did Washington’s views on slavery change? “George Washington began questioning slavery during the Revolutionary War.” In early 1776, Washington exchanged letters with Phillis Wheatley, an educated freed slave who became the first black American published author. As depicted in her poetry, she transformed from a loyalist into a patriot.

Likewise the heroism of Peter Salem at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775 was well known. Salem served four years in the army, including crossing the Delaware River in 1776.

The war also exposed Washington to officers who opposed slavery, such as John Laurens and the Marquis de Lafayette. A slave turned spy, James Armistead, gave Lafayette invaluable intelligence that led to victory at the Battle of Yorktown. A French officer observed that black soldiers made up a quarter of Washington’s Army at Yorktown, the war’s final major battle.

“As a young Virginia planter, Washington accepted slavery without apparent concern. But after the Revolutionary War, he began to feel burdened by his personal entanglement with slavery and uneasy about slavery’s effect on the nation.”

Washington wasn’t alone. Vermont outlawed slavery in 1777. A Massachusetts judge declared slavery unconstitutional at the war’s end.

“Throughout the 1780s and 1790s, Washington stated privately that he no longer wanted to be a slaveowner, that he did not want to buy and sell slaves or separate enslaved families, and that he supported a plan for gradual abolition in the United States.”

For most of his life, freeing slaves in his home state was illegal. After the war, freeing slaves became legal in Virginia.

“I never mean (unless some particular circumstance should compel me to it) to possess another slave by purchase: it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by the legislature by which slavery in the Country may be abolished by slow, sure, and imperceptible degrees,” Washington wrote in 1786.

Less than three years after his presidency, Washington died of a brief illness in December 1799. Within a couple of months, his will was published in newspapers around the country, giving Americans the opportunity to discover his countercultural decision to free the slaves under his direct care.

Any teaching or discussion of Washington and slavery, especially at the military academies, would benefit from including the facts and context that led him to change his views. Visit Mount Vernon’s website for more information.

Jane Hampton Cook is the author of The Burning of the White House and other books. She is the host of Red, White, Blue and You.

Leave a Comment