From STARRS Vice Chairman, Major General Joe Arbuckle, US Army ret:

The below article from the 1945 Infantry Journal came from a close personal friend, Mike Frazier. Mike was a Marine corporal in Vietnam, shot twice, and medivac’d. Mike has a long family history of serving our nation to include his dad and his father-in-law who were both army infantry in Europe; one wounded, both with CIBs and decorated.

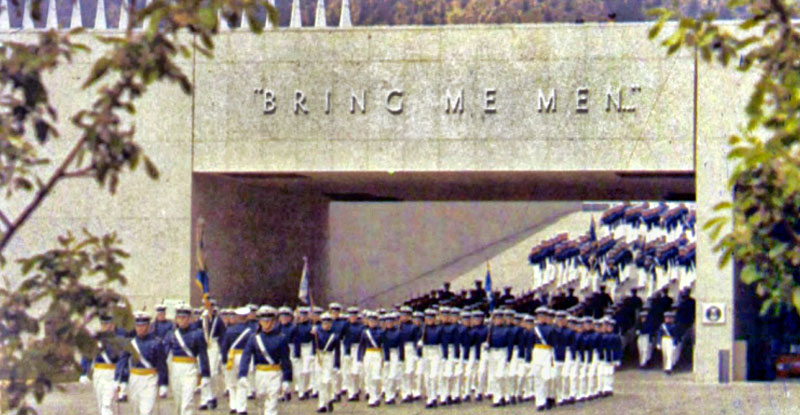

Mike was going through family records and came across the attached article which is timeless. It captures the essence of leadership which is largely forgotten today in our woke military, especially at the academies.

Above all, the most important leadership principle is “setting the right example”.

Closely related which was drilled into me/us is “know your men and take care of their welfare”. Added to that was, “be technically and tactically proficient”.

Nowhere were social programs like DEI ever considered.

Old Army: take care of the troops in the field with hot rations and dry socks… Add to that old adage, an occasional shower.

Thanks Mike, my warrior friend, for the timeless reminder.

Click graphic to enlarge:

INFANTRY JOURNAL, 1945

The leadership of troops in combat is the ultimate aim of all leadership.

And it is in combat that the proven leader and his men are either welded into a functioning fighting unit or fail in the great test.

The way in which a leader of a fighting unit does his job before and after combat bears directly upon success in battle.

The combat leader’s job is a full-time job —with overtime and plenty of it.

The same is true for the leaders of the thousands of units which may never operate under combat conditions.

They too must be on the job day and night, doing all a leader of troops must do to deserve the name.

In one way the job of such leaders is harder than that of the leaders of combat units.

If the combat leader has succeeded in forming a vital, efficient battle team, his outfit is all set for battle.

It has the battlecraft, the endurance that is needed.

It has, above all, the spirit of true fighting men in a fighting outfit.

But the leader whose troops do not go into battle cannot build up exactly this same spirit.

He can, however, build up a similar spirit.

He can create through the exercise of his ability as a leader a unit that tackles its work—its important supporting job—with a spirit that differs only a little from that with which combat units tackle the job of battle.

Leadership in the rear areas, far from the enemy, is just as important to the success of the whole Army as leadership in battle itself.

The leader in such conditions uses the same rules that any other leader does.

He must be loyal to his men.

He must never show disloyalty to his own superiors.

He must do his best to be cheerful and helpful no matter how unpleasant the military situation.

He must set an example for the men he leads—in appearance, actions, speech.

The leader must, perhaps about all things else, know his stuff.

He must continue to learn from every new situation, the better to look ahead to situations yet to arise.

The leader must know his men as individuals.

The small-unit leader especially must know every man by name, where he came from, what his particular abilities are, and what he is like.

Every man needs to feel that his squad, section, platoon, and company commanders know him.

No leader can afford to let any man in his outfit feel that he is just a serial number.

The leader in rear areas, just like the leader in combat must take care of his men.

He must see that their food is the best that can be obtained; that they get the clothing they need and the medical aids; that new men are welcomed warmly when they join the outfit.

A most important part of leadership is the availability of the leader to his men. His door must be open.

It is not possible to build a first-class unit unless every man knows he can go to his platoon or company commander with his personal troubles.

A leader has to be accessible to those he leads.

Men of all units, wherever they may be serving, will do their jobs better if they know why they are doing what they are doing.

In the words of Field Manual 21-50, “Nothing irritates American soldiers so much as to be left in the dark regarding the reason for things.”

The able leader sets high standards for the performance of all duties.

He tells his men, and proves it, that their own outfit is unexcelled.

He sees to it that men get praise when they deserve it.

He sees to it that passes, furloughs, and promotions are given out with absolute fairness—and punishments also.

The true leader is never arbitrary.

He holds his anger for the real emergencies of battle if he lets it go at all.

He never humiliates a man in the presence of his equals.

He backs up his noncoms, but at the same time sees to it that they carry out his own fair policies.

The leader in the rear areas, again just like the leader in the combat zones, meets every special situation realistically, thinking first of all of the welfare of his men.

He can never depend upon his insignia or rank alone.

It is true that these indicate his authority and that his men must obey his orders.

But there are a thousand things more to leadership than the marks of authority.

In any place, in any theater, in any branch of the Army, it takes a man plus stripes or insignia to be a leader.

Related:

STRENGTHENING THE PROFESSION: A CALL TO ALL ARMY LEADERS TO REVITALIZE OUR PROFESSIONAL DISCOURSE (Modern War Institute at West Point, 11 SEP 23)

By General Randy George, General Gary Brito and Sergeant Major of the Army Michael Weimer

. . . Our Army must reinvest in venues that produce vital professional discourse to improve our professional expertise. When we were leading companies, Infantry, Armor, and other branch magazines allowed us to learn from our peers, plan the best possible training, and see new ways of operating. . . .

. . . .In the interwar period before World War II, our greatest generals and warfighters contributed their thoughts to branch publications. In the Infantry Journal, then Major George C. Marshall wrote about “Profiting by War Experiences,” while then Major George S. Patton, Jr. contributed his thoughts on “Success in War.” Likewise, noncommissioned officers like Sergeant Terry Bull contributed articles on “Battle Practice” while Staff Sergeant Robert W. Gordon both wrote for and edited the journal. Their contributions demonstrated the strength of the profession by helping solve the real problems of the day. . . . .

Leave a Comment