By Lt Col Eric M. Vogel, USAF ret, USAFA ’73

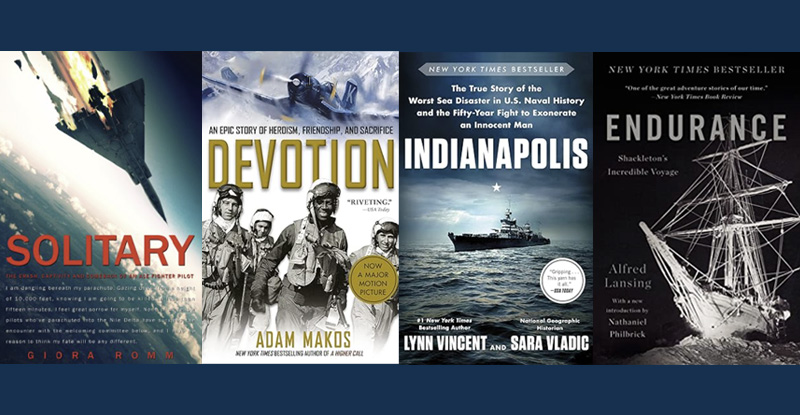

Solitary, Giora Romm (2014)

Devotion, Adam Makos (2015)

Indianapolis, Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic (2018)

Endurance, Alfred Lansing (2014)

All four of these books have simple, one-word titles, yet they recount incredible twentieth century stories. All four portray values and challenges that will resonate with members of STARRS. Taken together, they encompass suffering and tragedy, but also nobility and triumph.

Shot down, Imprisoned, Repatriated to Fight Again

Solitary is the vivid memoir of Israeli Fighter Pilot Giorra Romm. Shot down in his Mirage over the Nile Delta on September 11, 1969, during the War of Attrition, he is captured by the Egyptians. As a 22 year old lieutenant, Romm had become Israel’s first ace during the Six Day War of 1967, downing three MiG-17s and two MiG-15s.

A missile destroys his aircraft’s hydraulic system; the violence of the ensuing high-speed ejection breaks his left wrist and elbow. Descending in his parachute, he looks down and cannot see his right leg. As he turns his head, he sees it behind him, bent in the wrong direction. His right thigh is shattered.

Captured, he is exhausted and in tremendous pain. Romm struggles to keep his wits about him and maintain his honor.

Sayeed is in charge of Romm. Nadia is his respectful and caring nurse. Othman, his guard, plays the good cop/bad cop role, helping him become more comfortable at times, abusing him on other occasions. The “Sudanese Giant” beats him. He is intermittently starved.

Interrogations are a dangerous game and “become a riveting intellectual contest. What does the interrogator know?” Romm sometimes wonders if the interrogator’s questions are real, or a test of his veracity. But he retains his presence of mind and even asks about the status of Apollo 12.

He and another pilot are exchanged on December 6, 1969, for 72 Egyptian prisoners. As Romm is carried away, Sayeed becomes emotional, holds out his hand and says “It was an honor to know you, Captain.” Romm wishes to speak but the words get stuck in his throat. Sayeed adds “May God be with you.” (One wonders in 2023: What do members of Hamas say upon the release of their hostages?)

Romm recovers and returns to flying, serving as a squadron commander during the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. His love for his fellow pilots—peers and subordinates—is evident throughout the book, even more so after his prison experience. He thinks of them constantly—the deceased, the imprisoned, the active flyers–even while flying combat missions.

Two passages, among many memorable ones, stand out. First, as he lies in his cell in solitary, he turns to the wall in anguish. There he reads three phrases from a previous resident: “They know about you. They’ll get you home. It’ll be okay.”

Secondly, at the end of the book, Romm reflects on leadership. It is October 1973. From his military boarding school he learned that “whatever the mission assigned to you…it must be accomplished in full.”

From the air force and the squadron he commanded, he learned that “merely accomplishing the mission is not sufficient. You must strive to accomplish it as perfectly as possible.”

And from his father: “if the missions entails…unsavory deeds or a blatant disregard of principles…think twice about whether this aim is worth the bad taste it will leave for a long time to come.”

He summarizes his whole time in captivity in two words: “fear and loneliness.” Furthermore, two “counterweights” gave him comfort: “courage and self-control.”

Romm writes like he flies: focused, aware, and with passion. A great read, especially considering current events.

Brotherhood, Loyalty and Love

Amid the wartime action of Devotion, Adam Makos presents a theme of the nobility of love–of country, among fellow servicemen, and between spouses.

Based on today’s woke standards, Jesse Brown was born a victim of “Systemic Racism.” Growing up in Mississippi, he was taunted and spit on, restricted to the the back of the bus, and required to sit in the balcony of theaters. In the late 1940s, as an ensign in uniform, he and his wife had eggs thrown on them in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. None of this inhibited his desire to fly.

Tom Hudner, on the other hand, was from the world of “White Privilege,” according to woke thinking. Heir to a chain of grocery stores, graduate of Andover, he was destined for Harvard–but chose the Naval Academy (Chapter 8, “The Ring,” describes reactions to Tom’s Academy ring). Initially dreaming of going to sea aboard ships, he chooses to fly. Tom is a gracious gentleman and respectful of all people.

But both men benefited from an important privilege: both came from a two-parent family (the two-parent privilege was discussed in a fall STARRS Town Hall; see also The Two-Parent Privilege by Melissa S. Kearney).

Jesse’s father, John Brown, had served in the Army in WWI and was a sharecropper. His mother had taught school and served as a missionary in Mississippi. With their three children, they lived a wholesome home life of music, faith and books. Tom’s father, a Harvard graduate and officer in WWI, owned a chain of grocery stores. He and his wife raised five children in a close-knit family.

Despite Jesse’s experience with racism, it was not “systemic.” While in high school in Hattiesburg, he began working summers in the Holmes Club, a night club frequented by many soldiers from nearby Camp Shelby. One summer, on his last night before returning to Ohio State, the owner passed a hat. “The white soldiers of Camp Shelby tossed in wadded up bills, the bar owner emptied his wallet, and together they filled the hat with seven hundred dollars—enough for a year’s tuition.”

The services were finally formally desegregated in July, 1948 by President Truman. Nevertheless, during pilot training, several instructors refused to accept Jesse as a student.

Returning to his high school after earning his wings, Jesse revealed in a speech how he had succeeded while many black cadet students before him had failed. It was thanks to his flight instructor, Lt Roland Christensen. “Convince me you have what it takes” Christensen tells Jesse, seeing him “as a man, not as a black man.”

Jesse triumphs over adversity, eventually becoming the first black U.S. Navy carrier pilot.

Jesse and Tom end up in the same squadron at Quonset Point Naval Air Station, Rhode Island, flying the F8 Bearcat. Jesse is married to—and deeply in love with—Daisy, whom he met in High School. Jesse and Tom are living the dream, transition to the F4 Corsair, and become close friends–brothers in arms.

While on a cruise in the Mediterranean aboard the Leyte, war breaks out in Korea and they quickly return to San Diego and then sail to Korea, flying sorties in support of the Marines at the famous Chosin Reservoir.

Author Makos masterfully weaves the intense terror and harsh conditions of the ground combat units with the extraordinary efforts of the Corsair pilots to coordinate with–and defend–the Marines who are trapped.

Tom and Jesse remain linked as wingmen—but also in heart and soul. When Jesse’s engine fails and he is forced down, Tom attempts a rescue, for which he will receive the Medal of Honor. It is doubtful that any reader can keep a dry eye during this segment of the book.

This book overflows with devotion of many types: the friendship of Tom and Jesse; the unity of members of combat units–soldiers, sailors or airmen; and the patriotism exemplified by service to country.

And at the end of the book, we read the letter written by Jesse to Daisy the night before he died, underlining Jesse’s devotion to her and to God, so characteristic of Jesse’s entire life.

(Another great book by Makos: A Higher Call, is the story of a Luftwaffe pilot who declines to shoot down a severely crippled American B-17.)

Tragedy, Scapegoating, and Exoneration

Lynn Vincent and Sara Vladic’s Indianapolis is an excellent account of the worst sea disaster in the history of the U.S. Navy.

The cruiser USS Indianapolis, having just delivered components of the atomic bomb to Tinian Island, was en route to Leyte, Philippines from Guam.

Early on July 31, 1945, Indianapolis was struck by two torpedoes from a Japanese submarine; she exploded and quickly sank in the Philippine Sea. Approximately 300 men perished immediately; about 900 make it into the sea alive. Only 316 survive, the remaining men dying from shark attacks, drowning, dehydration and insanity.

Despite the horrifying situation of the three main groups spread out over the sea, the heroism and selflessness of individual sailors stand out as examples of leadership under extreme duress.

The rescue comes by chance, as search aircraft, looking for enemy ships and submarines, sight the Indianapolis oil slick—and then the specks bobbing in the water: the men.

Captain McVay is court martialed in December, 1945 for hazarding his ship by failure to “zigzag,” a maneuver which, in theory, inhibits enemy submarines from tracking a ship in preparation for a torpedo launch.

However, in some ways, he served as a scapegoat for the disaster.

Naval intelligence out of Guam failed to inform Captain McVay of specific, known threats which would have mandated the maneuver. The two commands which were charged with tracking ships in the area–and which shared a common boundary–assumed that the other was tracking the Indianapolis.

Furthermore, no one took note that the Indianapolis did not arrive at Leyte on schedule. During the court-martial, a number of officers were evasive, deflecting responsibility and blame.

This book covers three interconnected stories. The main story is the sinking of the Indianapolis and the rescue of survivors. The story of the court-martial follows, fascinating in its detail of the U.S. Navy system of justice and the recounting of the sinking by witnesses, including Mochitsura Hashimoto, commander of the enemy submarine.

Finally, there is the path to exonerate McVay by clearing his record. Commander William Toti, skipper of the L.A. Class nuclear submarine Indianapolis, namesake of the cruiser, completes a joint U.S navy/Japanese Navy exercise in 1997. The submarine will soon be decommissioned.

While in Japan, Toti sends a message to Hashimoto, commander of submarine I-58 which sank the Indianapolis. Thus begins the saga of exoneration, leading to hearings in front of the Senate Armed Services committee, headed by Senator John Warner, in 1999—practically a retrial of McVay—and ending with an entry in McVay’s service record exonerating him.

The surviving sailors of the Indianapolis—loyal to McVay–remained unified over the years, holding many reunions. They continued to respect him and longed for his exoneration—and concomitant peace for themselves as members of the Indianapolis crew. Unfortunately, a troubled McVay committed suicide in 1968.

This book is highly detailed, but never tiresome. It is well-documented and includes helpful maps and interesting photos of the main characters, both American and Japanese.

Fortitude, Leadership, and Solidarity

In the summer of 1914, Lord Ernest Shackleton sailed the Endurance, with 27 other men, 69 dogs and a cat, to Antarctica, with a plan to traverse the continent by foot. Alfred Lansing’s Endurance recounts their 17 month struggle to survive.

Just short of their destination, in December, 1914 the ship becomes frozen in the ice. Ten months later, they abandon the ship as it is crushed; in November, 1915 they watch it sink.

They drag three boats as sledges across the ice, facing further daily challenges: deteriorating ice floes, a lack of ocean free of ice for sailing, limited food (carefully divided rations, the dogs, then penguins and seals), and navigation difficulties.

Finally, in April, 1916, they are able to launch the boats, traveling 200 miles to Elephant Island.

From there, six of the men take the 23 foot whaler James Caird 650 miles to South Georgia Island.

Once there, they traverse the mountains to a whaling station. Shackleton borrows a boat from Chile and returns to rescue his men.

All survive.

There are two dominant takeaways from this wonderful saga. The 17 months of harsh conditions, daily stress, psychological challenges and constant dangers never end. As soon as one seems to ease—or be overcome—something else as harsh or worse occurs.

Secondly, it was the indomitable spirit of the crew, coupled with the superlative leadership of Shackleton, that allowed them to survive.

Shackleton had been masterful in selecting his crew (even the one stowaway ended up being of value and contributing to survival) for their expertise and abilities. None was perfect, but all were focused on returning home. Shackleton, for his part, inspired great trust and respect through his character, ability and intelligence.

He knew his men so very well: their skills and strengths, as well as their quirks and weaknesses. This knowledge was critical to survival in issuing orders, assigning them for duties, and grouping them in work parties, tents and boats.

Perhaps the most critical decision of all: who would be the six who sailed in 60 foot swells for 650 miles with rudimentary navigation equipment in an attempt to reach South Georgia Island?

Would that Shackleton–through AI–could appear at the USAF Academy 2024 National Character & Leadership Symposium. He would so eloquently explain that yes, we must “elevate the performance of our teams” (from the 2024 NCLS theme).

However, while doing so, he would also give the lie to any emphasis on diversity, equity and inclusion–that is, “expressive individualism” (see Strange New World by Carl R. Trueman)–over the unity of the team and strict focus on the goal of successful mission accomplishment.

All four of these books are among the best I have read in recent years; Endurance is one of the finest I have ever read.

As I reflected on their importance, I realized that many aspects of these books address—and support—the values of STARRS: Ability not Appearance; Unity not Division: Service not Self.

Choose several titles for your winter reading.

Leave a Comment