By J.A. Cauthen, retired Naval officer, USNA ’02

In June 2023, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. (SFFA) prevailed in complaints alleging racially discriminatory admissions practices at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. The 6-3 Supreme Court decision in these cases eliminated decades of ambiguity about what aspects of race were permissible in candidate evaluations at some of our nation’s most prestigious universities.

Following the Court’s decision, a number of analysts and commentators noted that Chief Justice Roberts’s majority opinion contained a footnote exempting military service academies. That footnote reads:

The United States as amicus curiae contends that race-based admissions programs further compelling interests at our Nation’s military academies. No military academy is a party to these cases, however, and none of the courts below addressed the propriety of race-based admissions systems in that context. This opinion also does not address the issue, in light of the potentially distinct interests that military academies may present.

Justice Sotomayor in dissent, joined by Justices Kagan and Jackson, argued that the Court’s majority did not “dispute [that] some uses of race are constitutionally permissible” and “agree[d] that a limited use of race is permissible in some college admissions programs”—notably at the nation’s military academies.

However, the liberal justices’ dissent incorrectly interpreted the footnote language as explicitly approving the use of race in admissions at military academies, due to the “potentially distinct interests” associated with military and national-security requirements.

This “exemption” or “carve-out” for military academies is nothing of the sort.

The Court’s majority simply explained that, because no “military academy is party to these cases,” their opinion did not address the issue. In a pending law-review article by Paul Larkin, Charles Stimson, and Thomas Spoehr, the authors write that the footnote merely articulates a point about the applicability of the majority judgment.

Harvard and UNC administrators, should they violate the judgment, can be held in contempt by district courts, but military academies and their leadership cannot because they were not party to the case.

Military academies, write Larkin et al., “will not be named in the corrected judgment that the respective district courts will enter on remand to reflect the Supreme Court’s decision.” Moreover, an “aggrieved party would need to file a new lawsuit to obtain relief.”

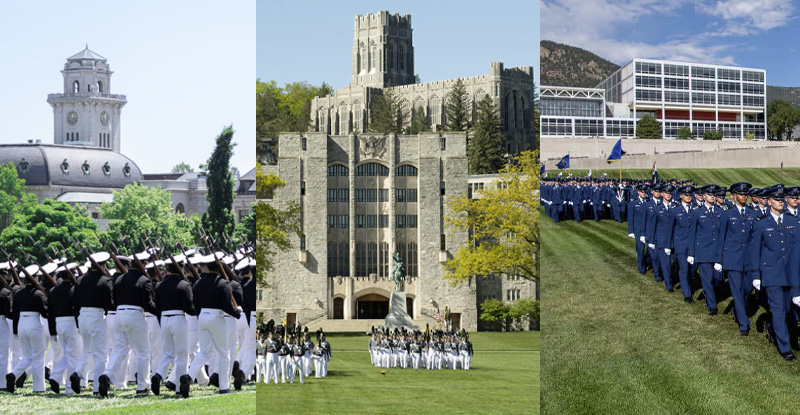

This is the process now unfolding with new complaints by SFFA against the U.S. Military Academy and the U.S. Naval Academy.

In short, SFFA argues that West Point and Annapolis focus inappropriately on race during the admissions process and that West Point’s “director of admissions brags that race is wholly determinative for hundreds if not thousands of applicants.”

As the Supreme Court articulated in SFFA v. Harvard and UNC, using race in admissions at public and private universities is incompatible with evolving jurisprudence concerning the Constitution’s colorblindness.

Chief Justice Roberts wrote in the majority opinion that “eliminating racial discrimination means eliminating all of it.”

Military academies, despite their unique function, are no more exempt from the Constitution’s demands than are Harvard, UNC, or any of the other academic institutions that are subject to our nation’s laws.

Moreover, the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause—or in the case of the service academies, the 5th Amendment’s Due Process Clause—cannot be informally or formally abrogated by the government or military. Should the state wish to do so, it must meet “a daunting two-step examination known as ‘strict scrutiny’” and prove that the “use of race is ‘narrowly tailored.’”

Military academies, like their civilian counterparts, cannot satisfy these tests, nor would they meet any of the other requirements laid out in the majority’s SFFA opinion. Among these are ensuring “sufficiently focused and measurable objectives warranting the use of race,” avoiding the use of “race in a negative manner,” avoiding “racial stereotyping,” and ensuring “meaningful end points.”

Despite the precedent set by the Court in SFFA v. Harvard and UNC, the U.S. government and advocacy groups remain intent on perpetuating discriminatory practices to achieve equality of outcome where race is concerned.

The federal government and sympathizers argue that the volunteer military’s good order and discipline, combat effectiveness, and esprit de corps are predicated on racially balanced force-composition—especially on an officer corps that racially and ethnically resembles civil society. Therefore, these voices argue, there is a direct compelling governmental interest related to national security, and military-academy admissions should be allowed to factor in race to achieve those ends.

This logic fails on multiple levels.

Although the courts have historically deferred to military judgment and expertise—in certain circumstances limiting the otherwise normal constitutional protections enjoyed by service members—this deference does not extend to civilians.

Larkin et al. highlight the key point that the majority of those applying to the military academies are civilians and not service members. Any constitutional constraints that might apply to service members do not apply to civilian academy candidates. The decision in SFFA v. Harvard and UNC must therefore also apply to military academies’ admissions processes.

The federal government and activists argue that crafting a racially balanced officer corps is a “strategic imperative” of grave national-security importance. Failing to do so would inhibit combat effectiveness, foment racial tensions between enlisted personnel and officers, and cede the battlespace to our enemies.

As Larkin et al. argue, however, the federal government and military offer no proof that combat effectiveness has been impaired or that racial animus is heightened because of numerical deviations in racial composition between enlisted personnel and officers.

To the contrary, a recent Department of Defense report noted that pervasive violent extremism, racial or otherwise, in the military is virtually non-existent.

Should our military really be a facsimile of civil society?

The political scientist Samuel P. Huntington, author of The Soldier and the State, was not convinced. Writing about the evolution of civil-military relations during the tumult of the 1970s and the transition to an all-volunteer military, he stated,

“The dilemma of military institutions in a liberal society can only be resolved satisfactorily by a military establishment that is different from but not distant from the society it serves.”

This differentiation from civil society is largely cultural and functional. In short, it is predicated on the application and management of state-sanctioned violence. Superficial racial and ethnic force-composition matters are secondary if not wholly irrelevant.

This false racial-balance-as-strategic-imperative argument is further discredited by simply examining the arbitrary racial classifications widely in use by American institutions, including the military academies.

Using myself as an example, I was born to a Taiwanese mother and a father of northern European ancestry. Should I be classified as White, Asian, Pacific Islander, or Other?

As the Supreme Court wrote in SFFA v. Harvard and UNC, “The use of these opaque racial categories undermines, instead of promotes, respondents’ goals.” The same holds true for the articulated objectives of the federal government and military vis-à-vis a racially balanced officer corps and admission to the military academies.

The notion of creating a military that is a perfect demographic reflection of the society it serves may also be impossible given the nation’s continuously shifting racial and ethnic milieu.

As SFFA v. Harvard and UNC made clear, “University programs must comply with strict scrutiny, they may never use race as a stereotype or negative, and—at some point—they must end.”

What holds true for civilian institutions is equally applicable to military academies: Any use of race to admit one group necessarily disfavors another group, perpetuates racial tropes and stereotypes, and, due to this nation’s increasing heterogeneity, will never have a “logical endpoint.”

Military professionalism demands differentiation between the military and the society it serves.

This does not mean the military should not superficially look like society, but it also does not mean it must superficially look like society. In fact, it may be more critical to have geographic and socioeconomic diversity than racial or ethnic diversity in a heterogeneous and pluralistic society like the United States.

By virtue of the congressional nomination process for military-academy appointments, aspects of geographic diversity are already infused into the process.

What the Supreme Court made clear is that using race as a determinative factor to reward some groups at the expense of others in the admissions process is pernicious, immoral, and counter to law and constitutional norms.

Military academies have no more compelling interest than do their civilian counterparts in elevating race above merit. They therefore must comply with the Court’s decision in SFFA v. Harvard and UNC.

Chief Justice Roberts eloquently said, “Many universities have for too long wrongly concluded that the touchstone of an individual’s identity is not challenges bested, skills built, or lessons learned, but the color of their skin. This Nation’s constitutional history does not tolerate that choice.”

Consequently, there can be no logical, legal, or constitutional basis for exceptions to this rule at our nation’s military academies.

J.A. Cauthen, a retired naval officer, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 2002 and taught in the history department from 2007 to 2010.

First published on James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal

Leave a Comment