Forrest L. Marion, Ph.D.

Retired U.S. Air Force officer and military historian

“In the U.S. military today, one wonders how much more damage to morale may be sustained by the thinning numbers of officers, junior leaders, and those in the ranks from the incessant attention granted by leadership to radical socioeconomic and far-left, domestic political priorities in lieu of legitimate national security ones. Every lofty announcement from a senior official, including at the Service secretariat level, that celebrates the latest so-called diversity or inclusivity initiative at the expense of meritocracy, or that touts the renaming of a military installation or a naval vessel as an act of high moral purity, dims a bit more “the light of battle in their eyes” and lowers “confidence in the higher command.”

Contrary to some, military history’s “cash value” is not because it provides a recipe for success in battle, but, rather, because it offers perspective on similar issues from past conflicts that bear on contemporary matters. In 2023 a little history from North Africa during World War Two is appropriate.

In the late summer of 1942, the Allies had yet to win a major land battle against the Axis powers. In the Pacific, the American fight against the Japanese at Guadalcanal was barely underway. In the Soviet Union, Hitler’s armies were soon to stall at Stalingrad but their defeat was months away.

In North Africa, Rommel’s Afrika Korps threatened to drive the British out of Egypt. That was until Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery arrived on 13 August and immediately began to rectify a confused, chaotic British chain of command in the desert accompanied by defeatist plans and mentality.

Montgomery wrote in his wartime journal:

Early in August 1942 the Eighth Army was in a bad state; the troops had their tails right down and there was no confidence in the higher command. It was clear that Rommel was preparing further attacks and the troops were looking over their shoulders for rear lines to which to withdraw. The Army plan of battle was that, if Rommel attacked, a withdrawal to rear lines would take place, and orders to this effect had been issued.

The whole ‘atmosphere’ was wrong. The troops knew that they were worthy of far better things than had ever come to them; they also knew that the higher command was to blame for the reverses that had been suffered.[i]

In barely three weeks’ time after Monty assumed command of Eighth Army, his leadership – including the complete reversal of plans to withdraw – produced the first major victory on land for the Allies, stealing the initiative from Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and ruining his chances for taking Egypt. Within the American-British inner core of the alliance (U.S., Great Britain, U.S.S.R.), Montgomery arguably achieved the turning point of the war against the Axis (for the Soviets, it was Stalingrad). Whatever character flaws and later wartime reversals some historians have emphasized, Monty’s genius and determination in the desert were transformative.

Fast forward to the last three decades. From the end of the Cold War until the last few years, U.S. military planning and operations emphasized regional conflicts, insurgencies, terrorism, and, for a time, “Military Operations Other Than War.” Competition termed “near peer” garnered little attention; the United States seemed peerless.

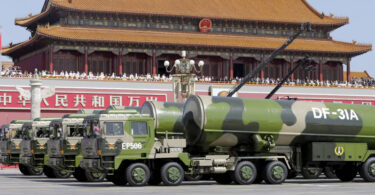

That has changed. There is open, serious discussion in official circles of the possibilities of a near peer fight with either Russia or the PRC.

Is the American military ready? Where is our Monty?

Is there any “confidence in the higher command”?

For several years, Russian and Chinese authoritarians have demonstrated both the will and ability to capitalize on American unseriousness regarding the security of her national assets and personnel, from an antisatellite weapon test that endangered the International Space Station as well as other spacecraft in the orbit of the space debris created (Russia, November 2021) to a near-collision of a navy jet with a U.S. Air Force (USAF) RC-135 in international airspace (China, December 2022) to – most recently – the violation of U.S. airspace by an unconventional surveillance balloon that went untouched until completing its mission (China, February 2023) to the intentional downing by an air force jet of a USAF MQ-9 remotely piloted aircraft in international airspace (Russia, March 2023).

The last two incidents in particular have elicited administration responses that are not encouraging to serious-minded, friendly observers. Such responses, not only unserious but perhaps unparalleled in their unrealism, have little effect other than creating grave doubts in the minds of many U.S. military members and citizens as to the rationality of their senior leadership, military and civilian.

Moreover, this unseriousness does not pass our adversaries unnoticed.

While the administration offers silly claims of not having engaged the Chinese spy balloon earlier for fear of endangering persons or property on the ground; and it clearly objects far more to the “environmentally unsound” means which contributed to the MQ-9’s destruction (dumping fuel on it) than to the fact of an attack against a U.S. aircraft, surely the Chinese and Russians continue doing high-fives behind closed doors.

Even more serious is the fact that our adversaries seem to understand far better than Washington does that there are cultural, psychological, and morale impacts within one’s military to ideologically-dictated lunacy on the part of leadership.

As Monty confided in his journal, “The whole ‘atmosphere’ [is] wrong.”

In September 1942, by which time it was clear that Rommel had been stopped, Montgomery wrote training instructions for the next phase of his planned offensive, including:

Morale is the big factor in war. Officers and other ranks have got to be imbued with that infectious optimism which comes from physical well-being; they must be brought to that stage of physical and mental fitness which will enable them to take on Germans (or anyone else) with complete confidence; they must be full of offensive eagerness and have the light of battle in their eyes.[ii]

In the U.S. military today, one wonders how much more damage to morale may be sustained by the thinning numbers of officers, junior leaders, and those in the ranks from the incessant attention granted by leadership to radical socioeconomic and far-left, domestic political priorities in lieu of legitimate national security ones.

Every lofty announcement from a senior official, including at the Service secretariat level, that celebrates the latest so-called diversity or inclusivity initiative at the expense of meritocracy, or that touts the renaming of a military installation or a naval vessel as an act of high moral purity, dims a bit more “the light of battle in their eyes” and lowers “confidence in the higher command.”

Notes:

[i] Nigel Hamilton, Monty: The Making of a General, 1887-1942 (New York, St. Louis: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1981), 588, 618-19 [emphasis in original].

[ii] Hamilton, Monty, 719, 741.

Forrest L. Marion, Ph.D., is a retired U.S. Air Force officer and military historian. He is the author of Flight Risk: The Coalition’s Air Advisory Mission in Afghanistan, 2005-2015 (Naval Institute Press, 2018), and (forthcoming), Standing Up Space Force: The Road to the Nation’s Sixth Armed Service (Naval Institute Press).

Leave a Comment