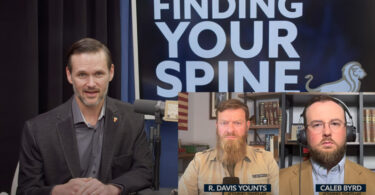

STARRS & STRIPES Interviews: Meet STARRS President and CEO Col. Ron Scott, PhD, USAF ret, USAFA ’73 — his experiences as a cadet at the US Air Force Academy, lessons from his Air Force military career and thoughts on the military today.

Have you ever wondered how a chance encounter can alter the course of your life? Join me, CDR Alan Palmer (USN ret), your STARRS & Stripes host, as I sit down with STARRS President Colonel Ron Scott (USAF ret) to unravel his remarkable journey to and through the Air Force Academy.

From a serendipitous meeting at his part-time job to the stringent mental and physical hurdles he overcame with the unwavering support of his father, Ron’s story is a testament to the transformative power of discipline and perseverance in military training. His insights into the challenging yet rewarding path from civilian life to becoming an Air Force officer are truly captivating.

From the radar squadrons in South Carolina to the mentorship from and of trailblazing leaders, Ron’s early career is filled with unexpected leadership roles and profound lessons. As an inspector general uncovering illegal activities and an officer navigating racially charged incidents, Ron’s experiences underscore the importance of readiness, accountability, and mentorship in military leadership. Through these gripping narratives, we explore the complex social issues within the military and the critical role that mentorship plays in shaping effective leaders.

Duty, respect, and Cold War relations take center stage as Ron and I dive into broader themes of military service. Balancing personal ambitions with core values such as integrity and excellence, we share personal anecdotes from our careers, including the tense experience of crossing from West to East Berlin during the Cold War.

We also discuss the evolving cultural dynamics within the military, the negative impact of diversity initiatives, and the ongoing commitment to building a better future for our warriors. This episode is a heartfelt tribute to the sacrifices and dedication of those who serve, offering listeners a profound understanding of the complexities and honor inherent in military life.

Watch:

Listen:

CLICK HERE to go to podcast page

Or listen via your favorite podcast platform.

0:09: Military Academy Experience and Discipline

14:45: Challenges and Lessons of Military Leadership

24:40: Duty, Respect, and Cold War Relations

35:02: Military Duty and Leadership Challenges

45:56: Cultural Challenges in Military Leadership

59:21: Building a Better Future for Warriors

TRANSCRIPTION

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Well, Al, when I think back to my high school days, both my parents, who were high school graduates my dad completed the GED while he was fighting the war in Korea knew that a college education was going to be very important and encouraged his, their three sons to pursue college. So at the time I was thinking Harvard, Princeton, Notre Dame In fact I had a baseball scholarship to Notre Dame. But one evening I was working part-time to start raising money for college at Taco Bell in Westminster, Colorado, and a gentleman that was one of my customers asked me if I was going to college and I said I hope so and wanted to know what I knew about the service academies. And I asked what’s a service academy? He said you know West Point, Annapolis, the Air Force Academy, which is pretty new. He said do you mind if I come visit with your parents and talk to them about the service academies? And so that set up a meeting. He described it was an Ivy League equivalent education, that you were guaranteed a job after graduation for at least five years and the education was world-class and at no cost. So it was a full-ride scholarship.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So I applied and ended up getting appointments to West Point in the Air Force Academy, and I picked the Air Force Academy because my mom, her first son leaving the nest, wasn’t happy about me going all the way to New York, so begged me to go to the Air Force Academy, which I did, and so my first impression of the Air Force Academy was getting dropped off at the ramp.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: The ramp is a portal with this long ramp that takes you up into the academy itself, and over that ramp was Bring Me Men, was the inscription, and so you look up that ramp and you see the chapel and the Front Range, the mountains, and so a lot of us didn’t realize that Bring Me Men was from a poem that talked about bring me men to match my mountains, and the whole thesis for that poem was bring me men who are prepared and motivated to achieve greatness, to do their duty, their responsibility for their country. And so it was a very emotional experience for me on day one, and it didn’t take long for me to realize that this was not going to be summer camp. That evening I was back on my door and it was an older cadet that wanted to remind us that start time. The next morning was like 5 am and I reached out my hand to say hi, I’m Ron Scott.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: And he looked at me insulting him.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: He says we’ll talk tomorrow. So pretty quick to immerse us into this environment, which was designed to be stressful and to start teaching us to muster our inner strength, discipline, all that sort of thing, to be worthy to serve our calling. So that was my initial impression.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: That was the transition from civilian life into the military which for most of us it can be sort of traumatic, but how did you do in getting through that right away?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: My dad did a lot to prepare me physical fitness wise. Every morning we were up at five and he was running me through pushups and sit-ups and he knew it was going to be important to be in good physical shape when I entered. And I have to tell you, al, that was one of the reasons why we lost a lot of my peers in the initial days. They just couldn’t keep up with the physical demands. The other part was discipline and not to take things personally. You know he already knew that they were going to shout at me and call me names like Dooley and other names and not to take it personally. That was part of the development experience.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So I have to thank my dad for sensing what was going to be needed to get me into the program, into the stride, the rhythm, and to stick out the four years to walk across that stage with my classmates. And I’ll tell you, over 1,400 entered the academy on that first day and 840 crossed the stage at graduation. We lost over 600 classmates because of the standards.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: So, but those standards was some of that kind of a mental stress on some of the cadets that they couldn’t handle.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Very much. So I mean a lot of them. I mean the first day after getting all their hair cut off and you know five or six shots and all these uniforms and everything else. It was a shock to a lot of these young men. It was just men in my day. So you know it was a huge change of life on day one.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: So it’s kind of like breaking down the civilian habits and things you’re used to, getting used to a new way of living in the military which includes discipline, self-control and getting over adversity long hours marching or doing penalty drills or confined, isn’t it? . .

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: It was and this notion of teamwork. I remember during Hell Week this is at the end of the first year we went through a week of pretty intense activities to include jogging in formation 10 miles underarms. At the end of that 10 mile, at the end of that 10-mile, and it was at mark time. It wasn’t even walking, it was mark time 10 miles, which is kind of a modified jog. We’re at the bottom of our dormitory and an upperclassman said you know, I don’t think you can beat me across that stretch of pavement. In other words, he was challenging me to a race and I thought it was a challenge that perhaps I could accept on behalf of my peers, my flight. I said, yes, sir. And so he starts out and I’m running next to him with my M1 rifle. I beat him across the line and so he marched me back to the formations, holding me for breaking ranks and leaving the rest of my classmates and pursuing individual activity.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So that told me that that was a test. An individual activity, so that told me that that was a test whether I wanted to put myself above or ahead of my peers, which really speaks to the second core value for the Air Force service before self, which is so powerful, so important. And so it was an important lesson for me, and I mean to this day that upperclassman and I are great friends. Lesson for me, and I mean to this day that upperclassman and I are great friends. But it was part of the training, part of the indoctrination, to understand that you’re part of something much bigger than yourself and teamwork is critical to that unity, cohesiveness. And so what we see happening today to the military is just such a is so opposite that with this diversity, equity, inclusion, they really start to emphasize identity, groups and subcultures and that sort of thing, and then it doesn’t matter what you contribute. In the end everybody’s equal. With this equity notion, equity notion and then inclusion, the deceptive part is we want you to be included provided you do not disagree with the ideology.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: You have to understand why diversity. And if you don’t, well you’re part of an extremist group. So did you have Starbucks and safe spaces and places you could go do study groups and stuff? I mean, that seems like it’s a change from those days. I remember my compatriots who went to the academies. It was pretty strict. I mean you had your bunk, you had your living space and then you had the outdoor drill space and then you had classrooms and that was kind of it.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Yeah, it was very Spartan in terms of simplifying your surroundings and now you’re purely focused on academics and athletics, character development type programs and that sort of thing.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So my first year we had what were called two off-duty privileges that first semester where we could leave the campus, but we had to be back by 5 pm, and so it was a chance for us to go back into civilization maybe go to a store, although we didn’t have money but to get back into the rest of society and then be back. And so it was very Spartan. We ate all our meals together at Mitchell Hall breakfast and dinner, and today it’s not like that it’s you come in it’s cafeteria style, you can go through a line and pick stuff up and whatever, and so, in my opinion, the activity that takes place at Mitchell Hall was such a critical part of our development as a warrior because you’re now dining with your fellow warriors.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Yes.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And there were protocols, discipline even at the table in terms of how we address a senior cadet, how we develop manners in terms of passing things at the table, proper ways of passing, and so, which reminds me, we had this book that everybody was issued called Decorum, and it involved all the traditions, the military traditions, in terms of how to introduce people how to set a table, yep, and so that’s gone now.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: And so what to talk about, what not to talk about?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Exactly so in my thinking. It was rigorous, it was Spartan, but it was so critical, I think, in terms of shaping the type of leadership that took us into Desert Storm. I mean, there was no doubt Desert Storm was a statement in terms of the superior technology and the importance of jointness, that concept, how we integrate forces to apply a tremendous warfighting capability. It was that type of training that developed us to be ready for that. I was a commander during Desert Storm and so I commanded a unique unit called Jackpot.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: I had five C-130s, and in those C-130s we had these modules that contained communications equipment and we had to take off at wartime gross rates of 25,000 pounds over normal operating weights, wartime gross rates of 25,000 pounds over normal operating weights. And because of that if we lost an engine we didn’t have what was called three engine climb capability, which is a typical requirement, and all crews were briefed that lost an engine on takeoff they had to land wings level in the desert. But the preparation for those types of activities in Desert Storm I trace back to my days, our days at the academy, and the preparation that took place.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Because some things it’s like tough luck, cadet, you’re going to have to do it anyway. Make it happen, right, right, make it happen right Right, and the big thing is certainly at the academies, but it was true, I think, in officer training school at the time as well, was developing people who could lead and who had the instincts but also the aptitude and the commitment to lead which meant you were honest and forthright with your people and took care of them, actually mentored them when you could.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: That’s something that’s a special characteristic that is not taught in college and it’s often not even taught in the workplace much anymore. But it is certainly an important part of the military. So for you how did that develop in you when you were leaving the academy and then going off to be a new lieutenant, a new brown bar? I mean, you didn’t pick up instant leadership. Everybody was going to follow you and say, yes, sir, I’ll do anything. You say, lieutenant, you had to learn from somebody who was that? Do anything you say, Lieutenant.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: You had to learn from somebody. Who was that? Al, just this last Thursday I was at Mitchell Hall with the entering class and one of the questions that Julie asked me was sir, at graduation, were you ready to be a Lieutenant in the Air Force? And what a great question. And my answer was I thought so, no. And what a great question. And my answer was I thought so, no. And so my first assignment was to a radar squadron in South Carolina, aiken, south Carolina. There were four officers a captain who was really supposed to be a major, you know major lieutenant, colonel billet, and three second lieutenants. And so I showed up and realized on day one I didn’t have a clue about what was going on at that base and so we had the commander at the time was stealing from the base, and because I was the second ranking individual, the most senior second lieutenant there, I was the inspector general and so I had.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: NCOs come to me and say, sir, the commander is doing some illegal things. And so now, because I’m the inspector general, I have to, you know, hear what he has to say, even though I’m thinking this is going to put me in a very awkward position with the commander has to say even though I’m thinking this is going to put me in a very awkward position with the commander. He said that the commander had put these forms together to purchase lawnmower parts. He said I work in the civil engineering department and all of our mowers are in good repair, so we didn’t need any lawn mower parts. And so I asked what do you think the money was used for? He said, well, it was at this particular hardware store.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And so I went and I interviewed the store manager. He said, oh yeah, the gentleman that came in, he was really nice. He says, yeah, this form says this, but what I need to purchase are a couple of power chainsaws. And so he took those home. And then another Form 9 was issued for other types of parts and I went and checked on that and he says “‘Oh no, yeah, that money wasn’t spent for this, it was spent for X linear feet of chain link fencing that was installed in his yard'”, so based on those two pieces of evidence.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: I notified my counterpart up at 23rd Division and he came down to Aiken and fired the commander. He gave him a choice. He had 10 years enlisted time, 10 years as an officer, so he was eligible for retirement officer. So he was eligible for retirement. He gave him the choice retiring without any decoration or face a court martial. So he elected to retire. And so that afternoon, after he basically fired the commander, he hired me now to take his place as the commander, as a second lieutenant.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And, so by then, I had been mentored by a senior master sergeant who was taking me around and showing me the ropes, uh, and even some of the nuanced things he said. You know, sometimes you’ll hear this, but here’s the type of question you need to ask to really get the right answer, or whatever. So I mean he was a true mentor, senior master sergeant. Now here as a second lieutenant, I’m commanding this remote radar squadron with 150 people and that was a real eye-opener for me that when you get that commission and you go on active duty, they’re not going to ask you if you’re ready. They’re going to assume you’re ready and we have to do what it takes to get ready. First of all, recognizing that we don’t know what we need to know and to find out how to get that information and who to trust and depend upon.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: A lot of on the job training.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Exactly so, as you went in from being a junior officer, now you’re maybe a captain. They used to say that being a captain in the Air Force or the Army or a lieutenant in the Navy is about the best place to be, because nobody expected all that much from you yet and you still had a lot of freedom to do things and you’re probably young enough to enjoy it.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: What do you?

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: think.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Well, I agree 100% with what you’re saying. But after Aiken, I go to Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, texas. Now I’m a first lieutenant and we had a racial incident at the base. So we talk about diversity, equity, inclusion and all the implications of that, whatever. So here I am, 1975, a first lieutenant. I get selected to be an investigation officer for this racial incident and so I’m in the wing commander’s office. Norma E Brown, colonel. Norma E Brown, 6940 Security Wing Commander First woman to command a wing here at Goodfellow Air Force Base, which was security service. Everything behind the fence was super classified, and so she’s briefing me on the incident. And then she stops and looks at me. She goes are you a chauvinist? I go, ma’am. First of all, I don’t even know what that word means. I might be, I don’t know, that’s right and she asked do you resent working for a woman, ma’am?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: I’m just very uncomfortable one-on-one with a full-bird colonel. I’m just a lowly lieutenant, and so once we got that out of the air, but so anyway, I do the investigation and I found the individuals involved were demonstrating racist activities. It involved a car with six black individuals trying to get access to the base so they could go to the NCO club to drink with their friends. They wouldn’t let them in because nobody had an ID card. Only two gates. So they back up, they go to the other gate. Meanwhile the security desk has been alerted and so about four or five additional security force individuals go to that other gate. And when the car showed up, a young airman goes up to the car, starts sticking his finger in the chest of people in the car, asking them if they had an ID card, and then, when they all said no, he got them all out of the car, spread eagle, to include a woman who was six months pregnant, flat on the face, spread eagle, and so they got him back in the car and they left, and so that was the incident, and so I found that their behavior was egregious. Every NCO involved. I recommended a letter of reprimand and an unfavorable information file which would keep them from promotion for two years. And for the squadron commander, who was a major, I recommended an Article 15 and to be relieved of command, and the wing commander agreed with all the recommendations.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And after that was done, I said ma’am, one last act that I did not document on paper, which I strongly encourage, is that you reach out to every single individual that was involved, on the victim and, on behalf of the United States Air Force, offer an apology. And she said if I do that, you know we risk a lawsuit. And I said, and rightfully so, I mean what we did was egregious. And so she did, and, to her amazement, every single individual was so gracious, thanking her for the apology, and nothing happened beyond that. And so that was an early experience for me that told me that you know, when we make a mistake, we need to fess up, admit we made a mistake and then correct it and press on, and that’s the way I dealt with all my supports after that Okay, you made a mistake.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: What are you going to do to correct it? Oh, this is what I’m going to do. Okay, did you learn something? Yes, sir, okay, don’t do it again Now, some mistakes involved a little bit more than you know. A pat on the butt and pressing on.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: But you know those were early impressions in the Air Force. And this is what 1975, almost 50 years ago, and now to see what’s happening with the COVID vaccinations that were forced upon our folks, that were experimental and not fully FDA approved. So some of the actions that took place during that episode in our recent history, in my opinion was wrong. That the senior leadership should apologize to those that were discharged without honorable conditions, invite them to come back in, expunge their records of any adverse information, et cetera, et cetera. That’s the way an institution heals you make a mistake, you admit it, you correct it and you press on.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: But that doesn’t seem to have happened in recent years, particularly with things like Afghanistan. There’s accountability is kind of lacking in places, to put it bluntly.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Big big time and I’ll tell you Al when we think about the Second World War. Big big time and I’ll tell you Al when we think about the Second World War.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: I mean that was a major war, but what separated America from the Axis powers?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: It was far more than a technology. It was the American character, a duty to seek justice over injustice. That was the power that America brought to that conflict, and right now we are failing in that regard big time.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Well too. And then after the war, both in Japan and also in Europe with Germany, we helped restore those societies to a workable condition. Actually, they became quite successful over the years, not because we had to, because it wasn’t usually done in the past but you’re right. We had that obligation to make things better if we could, and we did.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Which speaks to the Air Force Corps values.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: I know Army has their, their institutional values, the same with the Navy and the Marines, but for the Air Force, our three core values are integrity first, which speaks to a lot of what we just talked about, service before self and then excellence in all that we do, and so the reason I mention that is now I’m probably going to be criticized for what I’m about to say we have a graduate that was selected as Miss America recently, and she’s a beautiful woman, very talented, but now her obligations involve carrying out her duties as Miss America.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Carrying out her duties as Miss America. And my question is after four years at the Service Academy, which is designed to produce leaders for our Air Force and Space Force, now this stint with the Miss America takes her away from giving 100% to the Air Force. And so I don’t fault a person who wants to do that sort of thing, but that’s not service before self. And if you’ve got a passion and something else that does not directly result to fly, fight and win, then you need to make that choice and press with it. Otherwise, if your choice is fly, fight and win, then 100% of your investment is all the way in for that mission.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: And that’s happened before with student athletes who ended up going in to professional sports, some of them while they were in the service almost, and so they got out early, had special treatment, and then we didn’t get the benefit of their service that way.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Right, right, and that’s so, you know. I understand there’s some recruiting potential there, and a good approach was Chad Hennings. Chad Hennings was an outlander trophy from the Air Force Academy, which is like the Heisman Trophy, but for a lineman. Chad won the outlander trophy and was recruited to play football for the Dallas Cowboys, but he went to pilot training, was checked out in an A-10, and he fought during Desert Storm as an A-10 fighter pilot. And so once he had completed his obligation, he left the Air Force, joined the Reserves and then signed on with the Dallas Cowboys and has three Super Bowl rings from the Dallas Cowboys Now, to me, that’s an example of how a person can fulfill multiple passions without slighting one over the other. So it can be tricky, right.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: And that’s great that he does that, and there are a lot of people who have done that too. So what else did you do? That stands out among all those other things which so far, are a pretty good description of a successful career. What else happened to you?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Well, went to pilot training at Williams Air Force Base. It’s a great place to train. We only had one weather day and that was because one of the radar approach control antennas was washed away due to flooding. It wasn’t because we had that sort of thing, but from there to Sembach in West Germany as an OB-10 Bronco forward air controller and while there I got OH-58 and and AH1S Cobra helicopter time working with the army, but maybe the the most uh, memorable experience was traveling to Berlin.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Remember, we had West Berlin completely surrounded by this, this wall, and my wife and I traveled on flag orders, which these were documents that had the American flag at the top, and then it had language, three different languages, saying that we were traveling on behalf of the United States government.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: We were expected to go over into East Berlin unarmed, unescorted. So I’m in a service uniform, a captain, I’ve got wings over my chest, us insignias on the collar, and then captain. And so we showed up at Checkpoint Charlie. They verified that Mary had 20 marks to pay for the visa, which was 14 marks, which took place halfway across from the western sector to the eastern sector. It was about 100 yards between the two layers of a fence, and so they encouraged Mary to go on ahead because they wanted to brief me on what I was expected to do while I was over there, and so that took about 20 minutes. And so now, and they told me that halfway across there would be a chain link gate with an East German soldier with his AK-47 at port, arms blocking that gate, arms blocking that gate that I was to look past him, no eye-to-eye contact and just push the gate.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Open and push him out of the way as I continued into East Berlin and as advertising happened. I’m thinking there are no questions about that. Are you sure about that?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: I know, and so meanwhile, once I had pushed him out of the way, I could see Mary now at the other end with her hands on her hips, and I could see smoke coming out of her ears.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: This was in January. Where have you been?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: huh, everything was gray, and so I’m going. Hey, honey, please smile for the cameras. We can talk about this later.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Yeah, we can talk about this later.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So we were tailed. We had three gentlemen that followed us everywhere. They wanted us to visit what was considered their shopping district, which was really an eye-opener. You know, they had displays that might have one item on a shelf. That was it a shelf. That was that, uh, but the the big, the big thing they wanted us to do was to go to the most exclusive hotel slash restaurant in east berlin and to go in and really laugh and kind of be loud in our communications or whatever. And amazingly, and this was supposedly the, the gathering place for the elite in East Berlin and so we walked in and it was fairly full.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: As we were going to our table, I mean, it was dead silence. Everybody was looking over at this American. Well, these Americans in uniform, no less, as now they’re getting seated, and so we ordered a brandy and a coffee and a dessert. We’re out laughing and the looks we were getting was just priceless. But it was all part of the psychological operations. Berlin was an occupied city. The United States had every right to be anywhere it wanted to be in East Berlin, and it was just sending messages of these people that Americans are not afraid, and that was the most people.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: And most people in our country don’t understand that, because they haven’t traveled particularly to countries that are in stress or something for places that are real fun to be.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: They think everybody’s like us right, and so they kind of expect treatment and you got it in spades.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: the other way around.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: That’s amazing, and if Cindy could bring up the picture of the Soviet officers, there we go. Yes, the gentleman sitting down. When we were introduced this was at the Berlin Air Safety Center in West Berlin and this was the facility where the Nuremberg trials were held. So there was a tremendous historical significance. And this, the Berlin Air Safety Center, was the agency that controlled flights into and out of West Berlin. There were three corridors coming from the west and one corridor coming from the east into Berlin, and so that lieutenant colonel was on duty there representing the Soviet Union in regulating traffic there through the Berlin Air Safety Center.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So we were introduced to him. He at my my chest and saw my wings, and about that time the gentleman standing up says to me in fluent english he’s a lieutenant and former mig pilot on desk duty here in berlin, which explained why he was looking at my wings. And he said I’m a lieutenant and he calls me sir. And so what he was telling us, that gentleman with his hands in his pocket was the political officer there at the Berlin air safety center. So what an eye opener this. This took place in 1979, 1980, at the height of the cold war. Took place in 1979, 1980, at the height of the Cold War. But the expression on that Lieutenant Colonel’s face, once he looked at my chest, we got eye-to-eye contact and then he nodded that was, in my opinion, a chivalrous signal that recognized that I was a warrior on behalf of my nation as he was a warrior on behalf of his nation, and it was a type of mutual respect that is

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: very exclusive to the profession of arms. Okay, cindy, bring up this other one. Here’s another picture taken in Turkey. Now, this is years later, when I was commanding an operation, a C-130 operation, out of Incirlik, turkey, and this was in support of Kurdish refugees that were pushed up into the northern Iraqi mountains by Saddam Hussein. So I took a break, I was in civilian clothes this chain-link fence is right on the perimeter of Incirlik Air Base and so I was walking down the street and, all of a sudden, this little boy comes running over, stops in front of me and starts saluting.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And there was an old gentleman nearby and I asked her do you speak english? He goes, yes, I speak english, I go. Why is that boy saluting me? And he said sir, you have the walk of freedom.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: That really that was emotional For people in the rest of the world to realize that at this time now, this was what 1990? At this time in history of the world, the United States was truly respected and admired To include its armed forces that were in other parts of the world to bring safety and security to other people, and to do it with humility and a sense of grace and gratitude for having the opportunity to do something that was bigger than yourself.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So that’s, another good thing that the, you know, the military affords you. And anyway, it’s one of my favorite pictures because it reminds me of the duty we have to be worthy of that kind of respect and appreciation.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: But people have always looked at our military that way, you know, and we were the ones that were giving the kids food and baby dolls and clothing and stuff in Korea, doing the same thing in Vietnam, helping out communities, in spite of what the media sometimes wanted to portray us as. And I think our people, because they are generous and good people, want the best for the people that they come in contact with. That was probably true also in the Middle East, and yet that didn’t work out so well for us in the end.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: No, it didn’t, which is unfortunate. And that’s the challenge that people in uniform have, because we’re supposed to be apolitical, that we’re good soldiers and we salute smartly that we trust our senior leadership to not put their subordinates in positions that would compromise their integrity, their principles, that sort of thing. And so one of the concerns that the leadership of STARS has today is we are disappointed in that sense of appreciation in our senior ranks. I don’t want to single anybody out or whatever, but for people in uniform at the senior ranks who do not question the praxis of diversity, equity, inclusion, and by praxis I mean the employment of the application of, not the theory. The theory behind DEI is critical race theory, which stems from the Frankfurt School of Marxism.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: But the fact that we have senior leadership that hasn’t taken the blinders off to take a closer look at this stuff that we’re pushing upon our younger people in uniform is, in my opinion, borders on criminality, because we are putting our military in a situation where they are losing that character we I just talked about and now it’s becoming more identity oriented and subculture oriented and that sort of thing, and not a pluribus unum. I’m part of the American fighting force, prepared to go fight and win our nation’s wars where and when needed, and so we have concerns about our senior leadership. We have occasional individuals behind the scenes who’ll say, yeah, we agree with you and we’d like to be helpful, but too many choose not to be more visibly supportive of this effort, and so hopefully they convince them to have the courage to have a voice.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: But those are the same kind of people that you and I were. We went through that.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Why are they?

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: different. Is there something that’s happening later? In their careers that prompts them to be a little different in that regard. Is it careerism? Is it the next job when they’re retired?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: That’s the tricky part. I think my last assignment was running the ROTC program at Arizona State University.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: And for every cadet.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: A week before he commissioned or she commissioned, I sat down with them for an hour for a little mentoring session and I showed them the Air Force instruction that talked about what they’re looking for in a colonel to advance to Brigadier General. Political savviness was one of those attributes. Political savviness, I said. Now what that means is you understand the importance of values and how they may compete with other services when we’re looking for resources out of the defense budget and that sort of thing, the values that underwrite the nature of our mission and how we are prepared to go fight and win our nation’s wars.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So that’s political savviness. It deals with values that are important. It doesn’t mean political party savviness, where now we align with a political party or candidates. Yeah, our allegiance is not to individuals, it’s to the Constitution and understanding what that Constitution means. So that’s the political savviness. And you don’t need to wait until your colonel to start developing that attribute. It can start on day one as a second lieutenant.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So it was back then trying to teach these cadets, as they’re getting ready to move into the officer ranks, that every day was preparation for the next day and preparation for the next job, the next rank. And again, it was all based on a sense of duty to serve your nation in uniform and as a leader with the courage to do what was right, even if it was going to get you fired. I’ve been fired before but as it turns out, it resulted in probably the best assignment I could have gotten out of that job, because the individual that fired me realized that I took a spear for the organization, and so that was his way of recognizing that serves before self really did mean something. So there’s, I’ll tell you, al serving in the military, which you have, both Air Force and Navy.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: You know those cultures are very important and it really starts with our leadership, and you know it’s so powerful to get people to do the impossible and, you know, to put their life on the line, because they understand what they’re being asked to do is right and worthy. But the people I was privileged enough to serve with and under in the Air Force and the Navy were all exclusively really good people and they’re strong leaders and they had that view of their job. It’s more than just themselves. But then some of them, as time went on, they’re now out of the operational forces, the combat forces, and now they’re back behind the desk in Washington DC, which are two of the things that you probably don’t want to do too much in life. I had the opportunity to spend about three years back in Washington and couldn’t wait to get out, so do you think of some of that difference in climate, if you?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: will. There’s one word that, to me, speaks to what we’re dealing with, and it’s incentive. What’s the incentive? Sometimes the intangible incentives, like the sense of excellence or the sense of having done one’s duty even though you’ve had to make sacrifices in other areas. That’s an incentive, it’s an intrinsic reward that tells you that what you’ve done is worthy. Other incentives tend to be a little bit more tangible the financial rewards or the prestige or the power that comes with it. And so that’s the competition, the competition between the intangible doing one’s duty versus now becoming wealthy. And life as a flag officer retired flag officer can be very lucrative, sitting on boards with the defense industry or whatever, which all of a sudden, indirectly, kind of promote and reinforce the warmongers that think we should be in Ukraine spending all this money and treasure and I’m not justifying what Russia did, but there are other solutions that could be approached, but it seems right now we’ve got a lot of money involved in promoting that situation over there.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Well, you know that’s it can be important to our national defense. But I think we’ve got to. We’ve got to look at that national defense picture maybe a little more broadly at least in terms of what’s good for our troops and their families and making sure that they can do their job. You know, we’ve done things like we restricted them over the last several decades, with restrictive rules of engagement, difficult situations, constant short-term deployments.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And then when?

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: they get back. Well, gee, sorry, we got too many. We’ve got to let some of you go, or we’ll let you go because of vaccinations, as you pointed out earlier. That’s not a way to structure a force that’s going to be loyal and is going to stay around with you for the duration of the time that they might otherwise stick to retirement. How do we fix that?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Well, it’s all culture. And people forget that the root noun for culture is cult. We talk about cults that are bad. I mean people have committed suicide being part of cults.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Yeah, I remember one of those when I was in San Diego that were waiting for the spaceship to arrive. Right right. So yes, but you know the right set of people, but we are a band of brothers, are we not?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: We are.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Those of us signed up and as I used to like to tell my friends running outside, when you raise your hand and you swear that you’re going to obey the Constitution, defend the country, you’re off on the journey right then, but you don’t know exactly where you’re going to go. You don’t know how difficult or how easy it’s going to be. You don’t even know what the outcome is. And isn’t that kind of life anyway? To the ones that want to say we’re all going to end up in the same place, how?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: can you do that? Yeah, it’s a calling.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And that starts with the four years that a cadet is at an academy or a midshipman is at the Naval Academy. That culture should be instilling in these students that you’re part of a preparation, the preparation for a calling, which is more than the five years obligation. That’s just purely a financial. Okay, you know, five years of service, you know basically offsets the cost of getting that commission. But the idea is to inspire in these cadets and midshipmen the worthiness of the military profession. Has a calling to serve 20 or more years in service to their nation and then they can move on to a civilian life after that.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: I served 34 years, counting four years at the academy, initially thinking I’ll serve my five years. It’s a fair return on the investment. But once I immersed in the culture and wanting to be worthy of my peers and those that had realized that serving our nation in uniform is a calling, you know I wanted to be worthy of that and you know now you do what you need to do to not let them down. And so it’s a cultural thing. And right now I, in my opinion, the service academies are failing big time. As you know, dr Scott Sturman recently wrote an article about the culture at the academy and the the five and dive mentality where, okay, we serve five years and jump Go make a fortune in, and so that’s sad, in my opinion. And if the academies can’t change the culture where they actually inspire these cadets and midshipmen to see the worthiness and the value of serving their nation in uniform well beyond the five years, then I think that they start fulfilling their chartered mission from Congress.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: So it seems that one of the innate difficulties with training new leaders in the academies is having examples for them there and training for them there, done by people who have been there had the experience. I suspect that was more the case when you were there than is probably the case today, because today there’s a large percentage of the professors, instructors, that are actually not military.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: They’re coming from the civilian world and in the case, I think, of the military academy, I remember a figure of roughly 40% of the instructors were not ever in the military. So how do you teach that part of it to the cadets?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: You hit the nail on the head. When I was there, to my knowledge there was only one civilian faculty member and there was no thought of tenure or anything like that. He was from the State Department. He was a Foreign Service Officer I think he’d been an ambassador at one time so he was teaching international affairs or international relations and under the political science department.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And that was. That was interesting to a lot of cadets because even though a lot of them, you know, the State Department wasn’t where they were headed, they realized that sometimes the military works very closely. Well, not sometimes. Typically, the Defense Department works very closely with the State Department, and so it was an opportunity to realize some of the overlap that we had in terms of promoting security in the rest of the world. But he was the only civilian faculty member, to my knowledge, when I was there, and so now, like you said, it’s like 40% are civilian and they’re doing that because they think it increases.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Yeah, there we go. Thanks, cindy, for bringing that up, that it increases the quality of the education, and you know how do you measure the difference there? You know, a lot of our military folks had PhDs and whatever. And when you go to typical universities, not all courses are taught by PhDs. They’re taught by teacher’s, assistants and groups like that. So you’ve got a PhD that kind of oversees the department and maybe that particular area of expertise in the uh, in the department, but they’re not all phds and and the big thing is, they’re imparting knowledge, and so what we see now there are courses that are being offered, like. There’s a minor called diversity and inclusion and it involves a lot of sociology courses that oh, hold that picture right there. That gentleman in the top picture he’s third from the left second from the right is at that time, colonel Malham Waken. Colonel Waken, brigadier General Waken, was an institution within the institution and I’m sad to say that Mal passed away a little after midnight last night.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: I thought you talked about that, sorry.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Right, what a mentor. Mal Waken, mal Ham Waken, mentor, mal Waken, mal Ham Waken. In fact, earlier today, I was telling you that we’re trying to get the academy to issue a book to every incoming freshman at the academy, one of them being Integrity. First here by Mal Waken, or this one by Mal Waken. To me, these topics are far more relevant than diversity and inclusion. But that’s how far we have departed from the original essence of what the Academy is and what it does. So but I think it also extends a little further.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Even the senior leadership within the Pentagon. Some of them are in senior executive, even like the secretaries of the services. There’s one or two who’ve never been in the military, and yet there’s the senior official in the services, notably the Secretary of the Army and, I think, one of the other secretaries who are with the RAND Corporation as consultants on military matters like DEI. Right back to the services. Now they’re in charge of the service, if you will. So how are we getting to the kind of the example leadership that you need? When they show up, I mean, everybody goes. Well, that’s great, we’ll have shrimp and cocktails, but what else is new?

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Well, that’s going to be a tough nut to crack If we get the right president in office that recognizes how far we have departed from the armed forces that allowed us to go into Iraq and defeat Saddam Hussein so abruptly. We are on a very, very slippery slope to lose all of that, and so it’s going to require a commander in chief to come in to realize, kind of like Ronald Reagan did back in the 1980s, that we need to do something to get our military back up to the level that it needs to be. The world is far more dangerous today than it was in Reagan’s era. Yeah, we had this nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union, but it’s so much more complicated today and so much more dangerous, and our military is at the lowest numbers. It was as far back as 1947. The morale is in the toilet.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: As you know, cindy pulls the other sentiment from the website and whatever. She’s got a document on our website that I think is 150 pages now and you can read what people are saying Inside the military veterans, supporters of the military. We are in a very sad state of affairs right now. There we go. Thanks, cindy Yep.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: So, Ron, as you mentioned Ronald Reagan, I was in Washington when Reagan was elected and what we did then was Jimmy Carter decided the military was too visible a presence in Washington.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So anybody that?

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: wasn’t working in the Pentagon had to wear civilian clothes, except for on Wednesdays we could wear a uniform. So we all had to go out and buy a whole bunch of suits and ties and stuff. When Reagan was finally inaugurated, the hostages that were in Iran were freed and a couple of days later they landed at Andrews Air Force Base.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: I was there leading the Navy troops to welcome them home and Reagan wasn’t there, but Secretary Alexander Haig was General Haig, which was interesting, as you mentioned him earlier. But I guess what I’m saying is the atmosphere changed overnight with a new president who really had the military in mind, and that’s something to see.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: And I don’t think it’ll take a long time to recover. Once we get the right leadership installed at the very top, that ripples throughout the ranks very rapidly and, quite frankly, if I were president, I would probably remove all the existing four and three stars. Let them retire. Yeah, that’s it.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: Let them go and all the political appointees is under secretaries and all too audio, so we’ll get some new guys in here. I can’t tell you how much that changed overnight in Washington then when Reagan took over. I mean, it’s like the floodgates open and everybody was all of a sudden enthusiastic again, and the military did come back a lot from that.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: Yeah, it would recover very fast. You know George Washington wow, what a great history there. He led a civil engineering delegation to map out and chart the Western reaches of Virginia. He had a team of surveyors. He was 12 years old 12 years old and so I shared that with my debts in the ROTC program. I said, you know, here you all are well plus or minus 22 or so and wondering if you have what it takes to be a leader, I said, you know, look at Washington at the age of 12. He mastered what he needed to master in terms of surveying. He knew how to communicate and he was trusted to lead this delegation into the western reaches of Virginia.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: So there’s so much we can do if we’re ready for it and we want to do it. You know, those are the keys. There’s so much we can do if we’re ready for it and we want to do it. Those are the keys. And again that goes back to culture Inspiring people that they want to be part of this and they want to give 100% or more to what they’re doing and their reward is this whole notion of excellence. They don’t need a pat on the back, they don’t need a pay raise or anything like that.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: So we’ll get back to it. We’ll get back to it. Well, carl, listen, it’s so great to catch up with you, and thanks for sharing your history and how you survived all those years in the military, but also thank you for what you’re doing today to make sure that our warriors and our troops are safe. And hopefully that’s going to change for the positive here coming forward. We’ve got lots of work to do.

Col Ron Scott, USAF ret: We do and, al, I feel blessed that we’re on the same team and we’ve got victories ahead of us.

CDR Al Palmer, USN ret: We are sir and listen, thank you so much and to our audience. Thanks for tuning in and listening to us. You can find out more about STARRS by going to starrs.us on the internet and check us out. Thank you.

Leave a Comment